Finally…

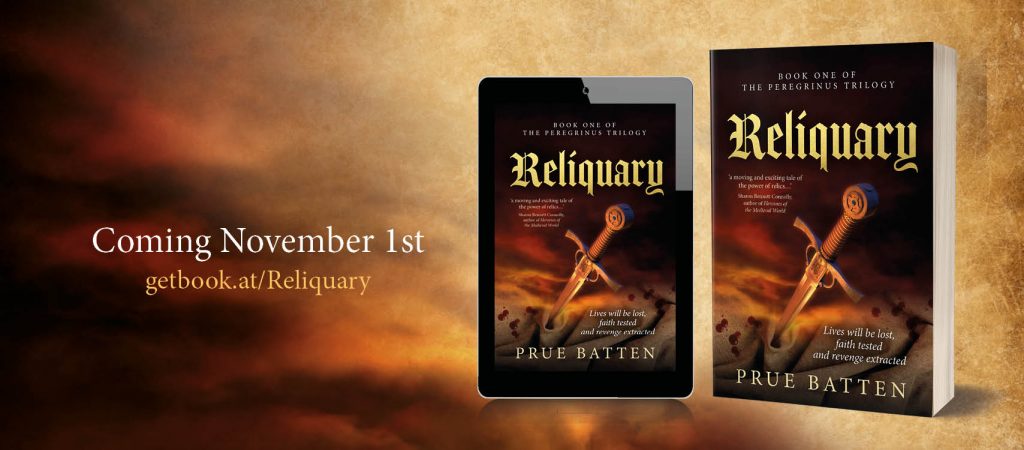

Finally… Reliquary, in both print and e-book, is published.

If I’m honest, I’ll say there were times I wondered if it would ever happen.

The biggest and most heartfelt reason was because my French researcher and great personal friend, Brian Cobb, died when I was perhaps half-way through writing the story. Brian had always been at the end of an email as my characters wound their way through France, but then sadly Soeur Cécile, Henri de Montbrison, Amée de Clochard and Petrus, the intriguing former Varangian had to find the way for themselves.

Brian left me with reams of information, being the perfect researcher that he was but it wasn’t quite the same without him seeing me over the line and both of us celebrating.

So, Brian, mon ami, Reliquary is for you!

*

When I write a book, I inevitably become close friends with the characters. We sleep together, eat together, fight together and Saints forbid, we live and die together. By the end of a narrative, I can tell you I hate finishing. It’s like standing at the departure gate and waving goodbye to folk one thinks one might never see again.

With that in mind, here’s a small excerpt from the first chapter:

The Journey…

‘Help me to see and understand the path that you have opened for me…’

Saint Benedict of Nursia

Chapter One

Soeur Cécile

Prieuré d’Esteil

1196 AD

‘We need a relic.’

‘Pardon,’ the Obedientiary put down her mug of watered wine and stared at the Prioress.

‘We need a relic,’ the Prioress replied. Younger than the Obedientiary, she had blue eyes. One could almost say guileless, had it not been for the veil of iron behind the heavenly colour. The Obedientiary had observed those eyes harden to moulded steel, and as strong, many times. Especially when senior prelates had visited the priory with the express purpose of wanting it closed because of its small population and lack of fame and fortune. As the Prioress spoke now, her eyes darkened – a tint reminiscent of the forge as the smithy honed blades for those who sought to arm themselves.

‘Something to bring the pilgrims,’ she continued, rubbing the worn edge of the table as if the smooth rhythm might settle the uneven nature of her thoughts. ‘In short, to bring us monies. We are only a few leagues away from the Chemin de Compostelle…’

In fact, the Obedientiary knew this. The Via Arvena, beloved of pilgrims, passed through Jumeaux, following the river that trickled and sometimes flowed, not far from Esteil.

‘I cannot fight off these crows of canons for much longer. I have been communicating with Mother Abbess at Fontevrault and she agrees that we must find a way to improve Esteil’s fortunes. In between times, she has said she will do what she can, but in my view, it will be little, perhaps nothing.’

Esteil was situated within Fontevrault’s purview. Occasionally, the mother house dispensed funds to smaller houses in times of distress. It also kept a weather eye on the spiritual wellbeing of the houses, but most small convents were expected to contribute to their continuance – temporal and spiritual. Survival of the fittest, thought the Obedientiary.

Outside, the wood pigeons cooed and the hens that lay smooth brown eggs pecked and clucked as if they understood the Prioress’s concerns. Someone walked past in clogs, the beat of their steps on the stones of the cloister the only sound apart from the birds. Perhaps the midday meal was done and the sisters were beginning to file out of the refectory to attend to their yard duties – the physic garden, the provender garden, the hens or the orchard. Or perhaps some of their small number were copying in the scriptorium, or stitching within the solar. Right now, the Obedientiary should be there, checking that her three stitching novices had begun their afternoon’s work on a cope while there was any sort of light.

‘And what is our value, Mère Gisela?’ she asked. ‘Are we any better or worse than other such small houses like ourselves? How do we argue our value when we are less than twenty sisters?’

‘Indeed, and despite what we do every day, what we accomplish in the scriptorium and with our threads, it is apparently not enough.’ The Prioress sighed and rubbed at the smooth skin of her hands. One folding over the other, rubbing this way, rubbing that as if her young bones ached. ‘God help us. Despite the quality of our scribes and the skill of our needlewomen, such work is not enough to plead our cause. Which is why I say we need a relic.’

‘Mère Gisela,’ the Obedientiary said, ‘we have no money with which to purchase a relic, even if we could find one. What coin we have must be put to daily survival. We are a poor house.’

‘And likely to remain so until our establishment is removed from us and we are sent to other places. Perhaps far from here.’ The Prioress slapped both hands on the arms of her chair and the crack of palm on wood resounded round the chamber.

Soeur Cécile’s stomach flipped over. The convent of Esteil was all she had known since she entered as a postulant, twenty-five years previous. It had provided her with warmth and succour and under God’s Divine Grace, she had become educated…

‘But I have a plan, Soeur Cécile,’ the Prioress’s voice had softened like butter left in the sun.

They sat alone in the Prioress’s dour chamber, a wooden platter of bread, cheese and watered wine between them. The Prioress, Gisela of Peslières, had broken the community rule of eating together in the refectory in this instance, and she had broken the rule of silence that accompanied eating. Cécile shifted, uncomfortable with the baldness of the meeting, hating the hard truths of the discussion, wanting life to continue its God-given rhythm. She moved her feet again. Her toes were cold in the worn sandals she wore around the priory. She hated clogs and would only slip them on when she had to venture to the gardens or the orchards.

She looked down at blue toes and uneven toenails. Underneath her sandals, the floor was rough-hewn – no rushes, just cold stone. Stone floor, stone walls and with warmth usually emitted by a brazier that filled the air with throat-catching smoke. Today, it remained unlit for which she thanked God. She preferred chill to smoke any day. She smoothed her hands over her coarse robes, faded black wool that offered a kind of protection in winter but when wet, became as heavy as the mud over which the sisters would walk in their clogs. In summer the rough-made robes were prickly and unkind, but then, God help me, Cécile thought, wasn’t that what being a sister was about? Suffering for God’s love?

I hope you’re enticed to read more, which you can do if you click on:

If you purchase it, a huge thank you and an even bigger thank you if you review it as well!

Leave a Comment