Reliquary – an author’s note…

The inspiration for my latest book, Reliquary, originally came from the research I carried out for the previous trilogy called The Triptych Chronicle. In the process of seeking facts on rare and valuable merchandise that may have been traded in the twelfth century, I came across mention of a silk called byssus and which is still harvested in the Mediterranean from a species of shellfish.

The sea mollusc called ‘pinna nobilis’ was known as far back as biblical times to be the source of the most curious cloth. The mollusc produces a fine filament that can be dried and then spun into silk so fine that a veil could be folded and placed in half of a walnut shell. One of the curious properties of byssus is that it can’t be dyed or painted upon, and it was an article posted by Paul Badde, on September 29, 2004 in the German daily Die Welt, that stirred my imagination.

At the time, he maintained that there was a sudarium with the image of a man upon it held in the small church of Santuario del Volto Santo in Mannopello, Italy. The image is rumoured to be Christ’s face which is pressed upon unpaintable byssus. He also maintains that this is the lost Veronica Veil.

Despite the world authority on byssus, Chiara Vigo, declaring the sudarium to be made of that rare silk, no one will know until scientific tests can confirm the cloth and the image, something the Capuchin friars of Mannopello would not allow at the time that Paul Badde’s original article was written. He has, since then, written a number of books on the search for the Holy Face.

His original article encouraged me to think about the value of relics to churches and their income, and I started reading about the history of relics. More particularly, I mused on the relic at Mannopello – supposedly made of byssus, the obscure cloth about which I had written in Michael, Book Three of The Triptych Chronicle.

Byssus intrigues me. The ancient nature of the cloth, the strange properties. This is a silk that by its very nature cannot be dyed, painted upon or marked in any way known to Man, so imagine the integral value of the Mannopello veil!

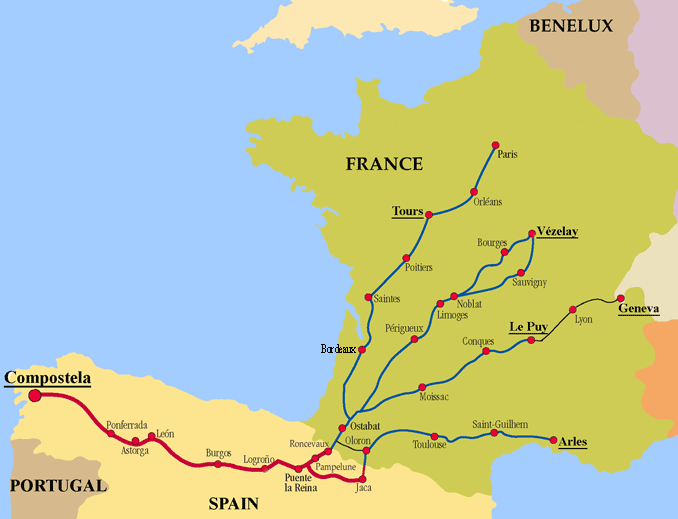

The research pathway brought me happily into the twelfth century where relics held great sway, and where the ‘pilgrim way’ was a Christian’s Gap Year through France, Spain, Italy and on to Jerusalem. The Pilgrim’s Way was marked with relics of real and dubious quality which were held not only by the Church, but traded with enthusiasm by merchants from, amongst other places, Constantinople.

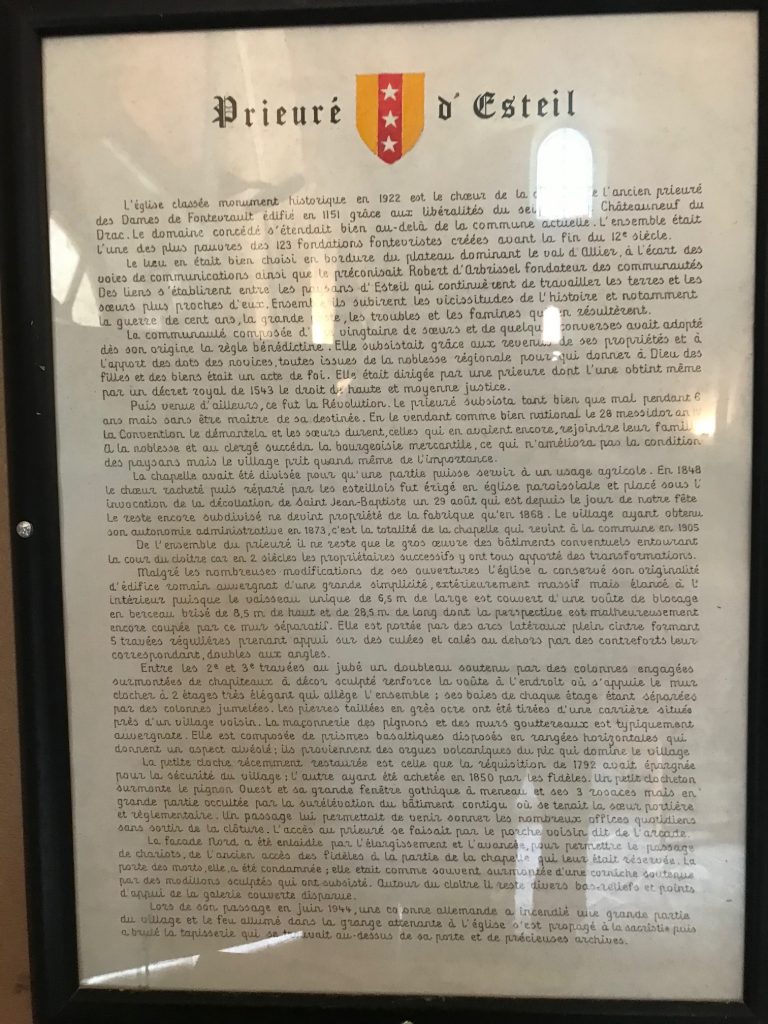

When French researcher and my close friend, the late Brian Cobb, found the remains of a little twelfth century convent in Esteil (pronouned Iss-toy), only a few kilometres from the Chemin de Compostelle, I began to have the whisperings of a story.

Add into that a twelfth century trading house with a reputation for finding the exotic, the rare and the secretive and my fingers itched to start writing. The people of the merchant house of Gisborne ben Simon were calling…

At no point did Brian or myself find evidence that the Prieuré d’Esteil had possession of a relic either in 1196 AD or at any other time, but I’m writing a fiction, and one could only wonder what the small convent did to survive in those difficult years, with a small agrarian population surrounding it and huge relic-laden abbeys like Conques, further along the road, and which effectively drew crowds of pilgrims who would bypass anything less.

I asked myself what would have happened to the priory if it had acquired a relic? More particularly, with the right sort of relic, what mayhem might have occurred trying to relocate the object from Constantinople to Esteil? Especially a relic rumoured to have been wrapped around the body of Christ.

That was the inspiration for the story.

As the research developed, actual historical individuals began to appear and although there is little detail on their lives, I was able to use their miniscule background to create threads to weave together through the narrative. Some disappeared, not to be heard of again, but in the case of the Prieuré d’Esteil, the Drac family was mildly notable. I have used the exact facts provided by the Prieuré d’Esteil about its donor, but there is very little more to be had in research across the board. This however, always plays into a fiction-writer’s hands. Unlike the well-documented king of the time, Philip of France, in whose service my main protagonist Henri de Montbrison fought in the Holy Land during the Third Crusade. History relates much on Philip and one can hardly veer from the truth.

The Third Crusade brings me to the concept of PTSD of fighting men in historical times. Was there such a thing? I would just like to offer up two links which were revelatory to me.

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/ancient-and-medieval-ptsd.html

A common and simplistic view has been no, there was no suffering because in previous societies, historians say violence was the norm. But many allusions from as far back in time as the Greek ancients to fourteenth century Geoffroi de Charny and beyond, indicate a number of common factors – lack of sleep caused by fear of night-terrors, overwhelming sadness, and mental images that could not be ameliorated. Thus, it seemed to me quite possible that my main protagonist, the above-mentioned Henri, should experience any one or a number of these, given what he endured in Outremer.

Could he lose his Faith because of the Third Crusade? One would think the Church, which after all approved the Crusade, would be able to provide an ethical and spiritual support to men on their return. But early on, I wanted Henri to be a thinking man, trying to rationalise what he had seen and done with what he had been taught of the overarching power of the Holy Trinity.

So yes, his Faith was tried significantly and found wanting.

The story journeys through the tail end of floods. The floods of 1196 did indeed happen and are documented. In March of that year, the Rhône valley amongst other areas, was subjected to an horrendous wet spring. It stopped the fighting between Richard Coeur de Lyon and Philip Augustus. It is said that only alms and prayers halted the rain and helped the waters recede.

I was able to use the subsequent halt of water transport on the Rhône and Saône, to slow Ariella’s journey to rue Ducanivet in Lyon, so that a fast-tracked, urgent overland message from Italy arrived in Lyon only a day after she herself had passed through the city gates.

Sometimes facts are just meant to be…

The above is just a brief journey through my inspiration and research for this latest book. What I love about researching is that extra facts are thrown in front of the writer and it’s a bit like a treasure hunt so that those unused facts are stowed away in a great casket, for the future. In addition, what always astonishes me is the way a character emerges from the narrative with a sidelong glance in my direction, whispering, ‘I may have a story for you…’

That has indeed happened with Reliquary and thus, I’ve begun researching and writing for ‘Oak Gall and Gold’, Book Two of The Peregrinus Series.

But that’s for another post perhaps…

This is all fascinating Prue – research is such fun, like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. I enjoyed the 13th century around the Cluny area where we had a house for 30 years. .

as above

The strange thing is, Jean, I set out with no real object and things begin to fall quite serendipitously into my hands.

I have to add too, that my dear late friend, Brian, was on a similar wavelength and seemed to understand what I might need even before I did. I am the poorer without him.

What an interesting read, Prue – thank you! And what a glorious image…

Thank you, Nicky. When one thinks the cloth is byssus and that the fabric has those amazing properties, it really sends shivers down the spine, I think.