‘Oh Christ! Oh Christ, the bairns…’

Over the years, I’ve often commented on how inspirational Dorothy Dunnett’s writing has been to me as I tread the path.

Once a couple of years ago, I was asked to write a piece for the Dorothy Dunnett Society’s august journal, Whispering Gallery, on the nature of shock or more particularly, what I found to be the most shocking piece of writing in Dunnett.

Dunnett is a master of the shock tactic and in truth, there are many incidents over The Lymond Chronicles and The House of Niccolo. But for me, ultimately it came down to one and it’s the one that gives this post its title: ‘Oh Christ! Oh Christ, the bairns…’ from Pawn in Frankincense.

It begins thus:

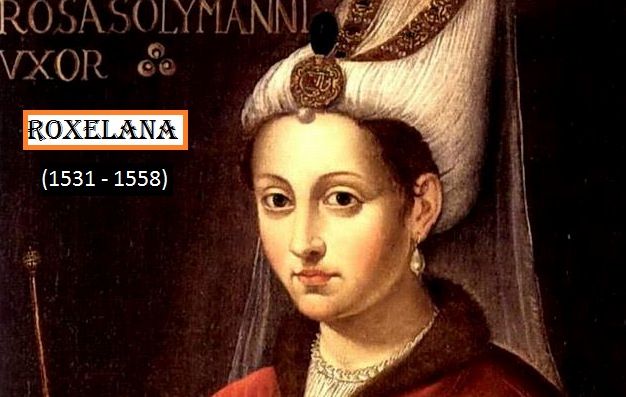

‘I propose that what has begun as a game, entangling as puppets who knows how many innocent as well as the guilty, should end in like fashion…I propose a game of live chess…’ Roxelana Sultán – PiF

I remember picking up Pawns to continue reading in bed one night, thirty-five years ago. I had been a devotee of Dunnett since reading Niccolo, and had moved onto Lymond, the man I called the human jigsaw because pieces to complete the puzzle were always missing.

The tension had built to a crescendo in the Palace of Suleiman the Magnificent and I thought at the time: ‘A human chess game? What’s the price for being removed from the board then? In what way can this possibly move the story forward unless it perhaps ends with Gabriel’s death? Because who else deserves to pay a heavy price?’

Was I to know at that point that a child might be removed? Or not?

That it may be the wrong one, or not?

Or that it would spin Lymond into infinite pain and self-loathing?

Or not?

Having already discovered Oonagh flayed and filled with straw (my other most shocking discovery), an unwilling part of me knew there would be a violent outcome to the chess game, so I read on, heart in my throat and my breath short.

The outcome of course, amongst the silk and tesserae of that selamlìk is legendary. The quiet brutality, the shriek of Gaultier … the heartbreaking massacre of an innocent…

Dunnett has a way of creating unforgiving drama with precision. The timbre of voices, facial expressions, refined movement within the room.

‘Still as a clock spinet… marking the hours, its case rimed with spectacular jewels; its inner wheels blindly spinning, awaiting the impersonal touch on the lever to trip it into a mechanical cascade of action. Which child to use for his checkmate? Which child to have killed?’

To me, the lack of emotion visibly evident in Roxelana and Lymond, the poignant kindness of Phillipa, the fire within Jerott and Marte are all such counterpoints to the bloody drama occurring in the corner of that seraglio room in Mìkàl’s arms. I often wonder how Dunnett, a mother of two sons, managed to write that scene. As a young mother of a blonde, blue-eyed son of Khaireddin’s age at the time of that first reading, I sat up in bed and cried. I was so drawn into the scene within the seraglio that all I could see was my own child.

It was… shocking.

These days I look back and wonder at the mastery, at the manipulation of the long-term in Dunnett’s hands. I always hoped Lymond would be united with his offspring and that all the pain might be worth it. But how clever was Dunnett to imply that the saved child might indeed be the wrong one? By doing so, she twisted the narrative once more, filling it with Lymond’s angst, with his need for complicated redemption of his soul. And the possibility of the saved child not being Lymond’s own meant that even in death, Gabriel could win. An abominable thought…

Having a reader guessing which son is Lymond’s right to the end of the series is the game play of a champion writer. I remember an interview where Dunnett commented that her publisher asked her not to reveal who the real son was and she reluctantly agreed. But then in that magnificently crafted way, she maintained she left hints for us all the entire way through the saga. I have to say I was so drawn into the brutal drama playing out that I missed every single hint and I am glad to this day.

One thing she did say, however, was: ‘Good and bad stock can produce indiscriminately good and bad offspring, and our environment can ruin what was potentially good. There is no place for prejudice. More than that, I am not going to spell out.’

Those words could almost indicate that terribly abused little Khaireddin, Lymond’s son or not, could never have lived, that there was indeed no hope.

There is no fear or favour in Dunnett’s style. She moves the story on, piece by damaged piece, slotting each scene in with mastered care, shock by undeniable shock. I could say that nothing shocked me by the end of that chess-game but I would be wrong.

Dunnett’s writing continues to un-leaven my sensibilities, even this many years later.

I’m in awe of her master-storytelling and will forever remain so.

Great essay, Prue. For me the most poignant lines are, ”Keep thy kisses. Thou art almost a man, and a man chooses to kiss only the persons he loves. Then thy kiss will be a big gift indeed …”

It’s a long while since I read the Lymond Chronicles but I’m still in awe of DD’s storytelling skill. I’m almost afraid to read the series again because it’s such an emotional roller-coaster.

Thank you, Juliet, for the praise.

The image of Lymond with the child and then the words you quote – heartwrenching. it actually makes my eyes prick. She wrote poetically, there’s no doubt, line after line filled with soul. Even now, the chess game reduces me to a shadow and despite that I know what happens to Gabriel, I find I still wish vehemently for his demise.