A Thousand Glass Flowers cont’d…

Chapter Three

Lalita

The tall gate blocked out the sunshine as Lalita tilted her head back to stare at it. They named it a door and yet it might as well have been an armoured portcullis. It was the entrance to a fortress, the gate beyond which no full-blooded male could proceed and which they named the Door of a Thousand Promises.

What promises? Promises of sex that an ordinary man might only dream of? Promises of untold wealth and comfort should an odalisque become known by the Sultan? Or promises of heavenly life in the hereafter because one had given up one’s freedom, one’s family and one’s life to serve the Court of the Sultan?

Or perhaps a thousand promises of a thousand terrible deaths should one enter uninvited.

A shiver rattled over Lalita. The door cast a shadow as black as the devil’s mouth and she stood in the middle of it, feet melded to the ground. The janissaries had turned away after the Grand Vizier knocked three times with the hilt of his scimitar and she felt as if each strike shortened her life that much more. Three enormous bars bolted the door, each connected to the other by elaborate scrolls indicating creatures: a scorpion, a spider, a snake. Lalita gasped as the first bar turned and rolled mechanically, the scorpion’s tail lifting to strike as the bar drew back. Then the spider’s fangs jumped forward as the next bar slid away. Finally, as the third bar withdrew, the cobra reared up, its hood spreading, the tongue flashing.

The doors began to open, peeling back to either side, a shaft of sun streaming out to her feet and blinding her. The Grand Vizier spoke and she heard his flywhisk tap as he ordered whoever was in front of her to take her to the Seraglio. Doves cooed, water trickled, music from lutes floated faintly in the distance and a tinkling laugh slipped into the air. Somewhere a dog barked and Phaeton gave an answering growl.

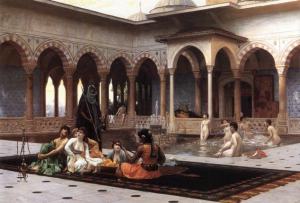

A firm push in the back set her walking, Phaeton stepping beside her, his damp nose nuzzling her hand. Still the glare filled her vision but she smelt civet, tuberose and lilies, the smell of lemons cutting through the sweetness of the perfume. Under her feet, she could hear the crunch of gravel and then the slap of her slippers on tiles as she was guided into a more subdued space, every smell, every sound with a sharpness that almost pained her. As her eyes adjusted to the softer light, she became aware she was in an elegant colonnade draped in roses. Alongside, as they stepped up from one shallow level to another, a rill flowed in a tiled channel, its murmurings creating a gentle ambience.

Lalita cast a glance at the man who guided her through these outer courtyards. He towered far above her shoulder, big with a loose body, one of the eunuchs who guarded the Seraglio. She knew these large white-clad men were mute and despaired to be part of a domain that saw the need to de-sex a man. To cut out his tongue so the flowers of the harem would only be for the Sultan’s plucking. Nothing, Arifa protect me, could be worse than this; not even if I were grabbed by Baghlet al Qebour of the Graveyards to be buried alive.

But she could not deny the beauty. She wanted to hate it, to find it disfigured. Instead her eyes wandered to the landscaped water gardens with massive tubs full of lemon, olive, bay and lime trees, to the tiles of floral enamels in ultramarine blue and viridian green. Remotely she wondered how easy it must be to create in such an environment because it stirred every sense. Already she had identified a design in the tiles that would wrap around the letter that began a paragraph. Why should I think of such things now? She sighed. Better that I think of prettiness than prisons.

The mute took her arm and led her to another door, this one carved less ferociously. They passed through a smaller colonnade where in the distance as she looked out, she could see gold leafed domes atop the palace. Even higher were the minarets and a square tower. Another door and the sounds of lute melodies and water playing became louder and then the final door was pushed aside.

The delicate notes dropped away, leaving only the rippling, running sound of water. Heads turned and curious eyes pinioned her, measuring and taking stock. Poisonous voices whispered behind organza veils, soft melting tones that stung her skin like nettles, denouncing her face, her hair, her clothes.

The delicate notes dropped away, leaving only the rippling, running sound of water. Heads turned and curious eyes pinioned her, measuring and taking stock. Poisonous voices whispered behind organza veils, soft melting tones that stung her skin like nettles, denouncing her face, her hair, her clothes.

She chanted silently, a mantra to uplift and strengthen. I am Lalita Khatoun, Arifa protect me, I am Lalita Khatoun. You are no better than me, I am no worse than you. But even so, her heartbeat bucked and reared like a trapped horse.

A massive man wearing a sumptuously embroidered robe levered himself off a divan, his eyes running over her as if he took an inventory. ‘You are the scribe?’

The sound of his herniated voice emcouraged hysterics but she stilled herself to answer. ‘I am.’

‘Salah will take you to your chamber. It is also your workroom. You will unpack and then Salah will take you to the baths where you will be prepared.’

‘Prepared for what? I am quite clean now, thank you.’

The other women snickered and the chief eunuch swung around and held up a pudgy palm. ‘Silence.’ The air vibrated with his voice as he turned back to Lalita. ‘I am the Kisla Agha and you will do as I say you must. You will be prepared for life in the Seraglio. You will have a certain polish, a certain standard. You may go.’

The afore-mentioned Salah came forward – an adolescent boy, golden and beautiful but oddly youthful, as if time had stopped for him years ago. Look at his dainty feet and his painted toenails, he is surely a plaything here. Phaeton licked her fingers. ‘My dog?’

‘The kennels,’ the Kisla Agha turned away.

No, no. ‘Please, sir, may I have your indulgence?’ She heard the odalisques suck in interested breaths but this big man they called the Kisla Agha merely inclined his head. ‘My dog is obedient. If I am to live alone in my own chamber so that I may work, and given that I am nowhere as lovely as the flowers already seated before me and shall never incur the interest of Sultan, I beg you sir, may my dog stay with me? He is my inspiration and this I truly need if I am to finish the book that is my commission from His Bright Light.’ She bowed her head.

The Kisla Agha’s eyes closed to slits and she guessed she was being weighed and measured. ‘You learn fast, woman. You understand the ways of these poisonous blossoms I think.’ He laughed with keen delight and the sound slid down her spine like a filleting knife. ‘Very well then, the dog shall stay with you. But your work must show the kind of inspiration of which you preach. If it does not, the dog’s life is forfeit. You are dismissed.’

Salah took her hand and led her away and as she left she heard vicious gossip and unkind threats hissed at her from amongst the silk and sarsenet-covered crowd.

‘Keep away, artisan.’

‘Be careful where you step, whore.’

‘A slip and you are done, slum bitch.’

She held her head high and walked on.

Salah simpered when they had gone through a further gate. ‘You took a risk, mistress. But I think you know that.’

Her head throbbed but she answered him anyway. ‘There are no risks for me at all now that I am here. I might as well be dead.’

‘Then you are a fool, mistress. Because when one chooses death in this place, it comes painfully and with great suffering. Would you wish the knowledge of such a thing on your family?’

Lalita remained silent but prayed for a djinn to fly in and scoop her up . . . she and Phaeton. As the thought ran, so the softest breeze blew over her forehead and cheeks and caressed her skin like a kiss, raising goosebumps and making her look around as if she would spy another person walking with her. But there were only rows of pleached lemon trees and hedges of oleander that twitched and shifted in a light breeze. Salah said no more, he was obviously not destined to be a friend, and drew her through a plain door of golden cedar, its silent latch turning.

‘These are your apartments.’ He led her past a lattice screen to a space with a divan covered in silk and wool quilts. ‘These are your sleeping quarters.’ And further past another screen. ‘Your workroom.’

A long table sat under tall windows that highlighted her working area. A stool had been pushed underneath the table and already a pile of pristine ivory paper sat waiting. Pots of paints and inks, sheaves of gold leaf, ceramic jars containing pens, brushes and burnishers lined the rear edge of the table. She put down her satchel and ran her fingers over the satin smooth of the paper. ‘This is magnificent.’

‘Of course, it is the Sultan’s own, made in the northern Raj with the finest flax from the Sultan’s own crops. What did you expect?’

She turned to him, anger bubbling at his arrogance. ‘I expected nothing,’ she snapped. ‘Just as I didn’t expect this morning when I woke up, to be incarcerated here for the rest of my life.’

He shrugged and his little boy’s voice answered her back. ‘That is the nub, Lady. The rest of your life. So let us go to the baths and the mistresses there can make you look at least as if you might belong.’

She could tell he was growing bored and no doubt longed to be back with the rest of the retinue as they jumped to the commands of the cosseted odalisques in the courtyards. She dropped her bag to the floor, along with a coverlet off the divan and bade Phaeton stay, knowing he wouldn’t move and would protect her satchel until she returned. Then without looking into Salah’s eyes, she walked past him to the door. ‘Show me the way.’

She reclined in the scented water and let the warmth sooth her nerves. The bath-mistresses had plucked her eyebrows finely, shaped her nails and clucked at the ultramarine smear. As they tried to draw henna tattoos on her face and hands, she pulled back and swore at them, at which they had pinched and grabbed her to lead her to the baths, thrusting her down the marble steps into the heavily scented water. Then mercifully, they left her.

She pushed some rose petals around with her fingers as she listened to the trickle of water into the massive pools. The baths were fogged with drifting eddies of steam and the quiet echo of drips underlined her solitude. The petals blurred as tears filled her eyes.

Uncle and Aunt, what will you say when you know? And Kholi my brother . . . if you were in Ahmadabad, this would never have happened. You would have loaded me on Mogu and we’d have beaten a path over the Goti Range after you had killed Kurdeesh, for you would have I’m sure, and fed him in pieces to the jackals.

As she thought of Kholi, a familiar black shroud slid up over her shoulders and she remembered its inception. She was working on an illumination, the gold letter entwined with a crimson rose and her throat closed in a spasm of such pain that she jerked the hand that held the paintbrush and a drop of red splashed onto the pristine body of the paper like a clot of blood. She threw down the brush and stood, clutching her throat, gasping as she tried to suck in air and then as quickly as it started, it ceased. She subsided onto her stool, her fingers trembling and as she stared at that crimson splash, a melancholia seeped over her and had stayed with her ever since. She dared not tell Soraya and Imran but her belief was that Kholi, her loved brother, was dead. Just like her parents. And now the gathered tears rolled down her cheeks and she forbore to dash them away because they lanced her pain and loss.

‘Why do you cry, Flower? Your fate is sealed. Better to accept it and stop such weakness.’

Lalita jumped, her head with its wet trailing ringlets flinging up as she grasped the white lawn sheet tightly against her body, casting glances left and right.

‘Here, I am here.’ The voice echoed from a particularly dense cloud of steam.

‘Where?’ She walked towards the fog.

‘Behind you!’

She turned, the water dragging at the sheet. ‘Show yourself.’ The words hiccupped out as her sobs became more audible.

‘Look up and cease wailing.’

She thrust back her head and there seated on the carved acanthus leaf platform at the top of a column sat a little sprite, his malicious eyes sloping up at the corners, his unkind grin smacking of teasing and worse. ‘An afrit!’ The tears stopped as if dammed.

The sprite manifested next to her with such speed that she sat with a thump on the marble steps, trying to make the sign of the horn with one hand whilst holding the sheet around her body with the other.

‘Huh, that sign will do you precious good now, snivel-nose, for I am here.’

Lalita stared at the fellow, aware that an afrit could be as evil as the worst djinn.

‘So yes, I am an afrit. I call these baths my home and even Lalla Rekya Bint El Khamar cannot scare me away from here. Oh no, Lady Rekya, Daughter of the Red One! She may think the bathhouse is her domain, but it is not.’ The afrit yelled this last to the walls. ‘So little wet flower with the crushed petals,’ he flicked her limp hair. ‘Morbid, are you?’

‘No.’

The afrit looked at her and cocked a fine eyebrow, smoothing the dark silk of his trousers. ‘You should be. You are here for life you know, and you will spend every waking minute preparing yourself to please the Sultan and fending off the murderous and secretive attacks of your sister odalisques.’

Lalita looked down at her puckered fingers. ‘You paint a charming picture.’

‘Sarcasm is the wit of fools, woman. What I say is truth and had best be faced. Especially by one such as you who has lost all her family and no doubt wishes to be spirited away by some djinn or other.’

‘How . . . oh! Was it you that brushed past me like a breeze in the colonnade?’

‘Maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t. Or maybe it was the spirit of your dead brother.’

The afrit cast her a sly glance and it struck her hard. ‘What? What do you say?’ She scrambled to the top of the steps. ‘What do you know of my brother?’ She began to shout as the steam rolled in front of her, obscuring her view of the obnoxious Other. ‘Tell me you foul little thing, tell me.’

Her yells echoed through the marbled bathing halls and the mistresses came running, their feet slapping on the wet tiles. Two of the mutes joined them armed with scimitars, and noise and shouting rang out as the women dragged her from the pool-steps. She pushed at their fingers but when the mutes returned from surveying the steamy corners of the hammam, she screamed at them all. ‘You idiotic halfwits, it was an afrit. Fools, open your eyes and you will see him. He was on the steps and up on that column and . . .’ her voice trickled to a stop as she observed their expressions. They think I’m mad.

She snorted. One of the mistresses grabbed her and she snarled at the woman whose face paled. Holding her sheet tight, she was propelled into a room where they fettered her hands and unwrapped her, anointing her with more floral oils and brushing her hair until it lay in a silken fall over her shoulders. As they completed her toilette, they watched her closely. The two mutes stood by as they released her hands and tiredness swamped her so that she let them do what they must. A kaftan dropped over her head, trousers held while she stepped into them. Oyster silk settled over her body and they wound pearls through her hair and around her wrists. Then the bath mistresses nodded and called Salah to take her back to her apartment.

As they walked, he looked her over. ‘More like an odalisque now, less like a cheap artisan. You know the word is already traveling through the chambers that you are somewhat unique.’

‘Mad, you mean.’

‘Insane. They say you maintain you spoke to an afrit.’

‘And if I did?’

‘Then you are truly addled, Lady. Others have never been able to enter the Palace. There are charms everywhere.’

‘Then obviously I did not see an afrit.’

Salah laughed. ‘Lady, I suggest you do what you must here and in the process keep yourself hidden. You have drawn unfavourable attention all too quickly and I warn you that mad or not, already you are seen as a threat by many of the Flowers and they are nowhere as delicate as they look. They will remove competition as if you were a crumb on the table. Trust me Lalita, they have far more experience in matters of competition than you and they contrive to win. Always.’

He opened her apartment door and left her as her spirit spiraled and Phaeton’s tongue licked her. Hearing the door click behind her, she quickly turned the key in the lock and sank to the floor like blossom falling from a tree, cuddling the hound close. ‘Phaeton, we have lost everything and may lose our lives here. I swear we are in the Underworld.’

Chapter Four

Finnian

Finnian’s memories boiled as the galliot approached mortal Bressay. Thoughts of revenge for an unworthy life impelled him. He would find the charms. How it will crucify the old woman. In so many ways.

He dredged through his recall, pulling at everything she had ever said about the Cantrips. She had mentioned a mortal, he remembered that – she believed the woman who had killed his brother had the charms, he couldn’t recall why. So often he listened without hearing – drunk and beyond the pale, but it was the crone’s sarcasm at the death of his brother that awakened his attention. ‘Another of your wretched line gone, and at the hands of a mortal.’ She laughed. The detail that followed such bald truth became explicit.

‘She’s a Di Accia and lived in Veniche and I feel it in my guts that if she had the instrument of your brother’s death, one of those charms sequestred so long ago, then she had the others. It’s a question of searching her domicile, an easy task as the woman is dead. Her palazzo is a museum, nothing has been touched, so if the Cantrips are there . . .’

She dragged him down to her level as she sat at the table. ‘Do you know what they can do?’ Her eyes sparkled with rapturous cruelty as she began to tell the oft-repeated story. ‘Long ago during the Wars of Chaos, one of them was used, the one they called Earth. And do you know what happened when the charm-master called out the spell? Every single walking creature, two legged or four, six or eight, everything,’ she paused and swigged her wine. ‘Everything within miles, whether on the battlefield or no, died in unparalleled agony so that Færan enemies were vanquished and the Wars were won. There was a sea of dead with not a drop of blood spilled. Just acre upon acre of twisted wrecks and for hundreds of years nothing has grown where the dead lay and Eirie quaked at that power. Even now the Vale of Kush is a desolate place. Can you imagine?’ She licked her lips and spat a pip from a grape onto the table without waiting for comment. ‘That idiot charm-master and the elders looked at what they had done and thought such destruction was contemptible and hid the charms. Fools.’

‘Did the charms not also kill Færan and other innocents? What’s the point?’

‘Tuh,’ she glowered in a half-drunk mood, oblivious to his stirring of her pot. ‘The point is that a point was made. No matter the consequence. Every living thing knew that whoever held the charms, held power over an entire universe.’

The point is that a point was made and for one moment now, he wondered if the point that he wanted to make was worth the killing of innocents in the process. He twitched his shoulder, feeling the puckered scars of child’s lifetime. Yes.

As the crew moored the galliot, Finnian leaped ashore, his body quickly finding its landlegs. He grabbed a longshoreman walking toward a pile of crates that were filled with a cacophony of frenzied feathers. ‘Ho sir, a moment.’ He slipped some gelt into the man’s calloused palm. ‘The next ship for Veniche, where is it?’

The man stared at the pile of money and grinned, licking his lips, turning to point across the weaving crowd. ‘The Pourpoint, sir. She leaves in a half-hour.’

Finnian nodded and walked away wafting a mesmer, leaving the man unaware of having spoken to anyone, confused at the gelt jingling in his palm. In moments, he stood dwarfed by the hull of the caravel that would transport him to Veniche. Its sloping bow dropped away amidships and men ran across the decks as a foghorn voice yelled commands. Sailors clambered up the rigging of the mainmast and leaned over the yardarm, belaying ropes. He walked up the gangplank and was accosted by an officer of the watch who put an arm firmly against his chest.

‘Yer name, sor. I’ve to check it off the lists.’

Finnian smiled, his hand moving slightly, a name appearing on the paper in the man’s hands. ‘Finnian. F-I-N-N-I-A-N. I’m sure you’ll find it there. I booked the largest cabin.’

‘Finnian, Finnian . . . hmm,’ the fellow glanced down. ‘Ah yeah. Cabin next to the Captain. Follow me, sor.’

The officer, a burly fellow in a faded but neat blue coat, a crinkled white shirt and with his hair oiled and plaited, led off across the sloping decks. Finnian liked the cut of the chap, amused at his rolling gait, as if the decks slipped away beneath the large feet. Bending his height beneath the doorframe as the fellow had done, he imbibed the smell of musty canvas and the fragrances of spices and of bales of silks and wools drifting from the hold.

‘It’s a good smell now sor, but in a few days, ye’ll be wantin’ to spend more time topside than here, I tell yer. It gets frightful stale. Here we are then, second biggest. Captain has the biggest and ye’ll eat all yer meals with him. We’re underway in fifteen minutes and if yer on deck, keep clear of the crew, they’ll be frightful busy!’

The door click behind as the fellow left and Finnian’s gaze absorbed everything of his home over the next week or so. Golden planks lined the walls, the caulking between gone black with mildew and age. A lamp swung gently, echoing the undulations of the hammock. An open chest was piled with neatly folded blankets and topped with a pillow, and a tiny desk clung to a wall. A chair was jammed underneath as if the mighty seas yet to be faced might tip them up and smash them like matchsticks. Pleasure smoothed senses that had been ruffled and knotted since the conversation with the water-wight. He examined the ship-shape nature of his cabin and knew he would be more comfortable than on the open galliot that had not only induced windburn but what the sailors referred to as ‘gunwhale-bum.’ Familiarity with the sea had been gleaned from the foul mouths of the weathered rejects around Castello but this vessel was no galliot filled with murderers, to be sure.

Muffled footsteps vibrated back and forth above him, the previous random pattern gone as a precision-drilled procedure began, the mooring ropes hauled in by chanting men. He hurried topside as a fresh breeze sang through the shrouds and the foresail and the lateen aft’sail filled gently enough for the caravel to slide away from the wharves. Below them on the docks, a well-dressed merchant shouted, shaking his fist. The sailors jeered back, swearing and laughing.

‘What goes?’ Finnian nudged a young fellow, the cabinboy, who scurried past with a mop and broom and shadows that spoke of tiredness and overwork looped under his eyes.

‘He reckons he had a booking, sir. But there’s none by his name on the lists, only you sir, and the Raji ambassador who’s traveling to Veniche. And he’s already chucking up half of yesterday’s dinner and we aren’t even off the harbour yet. I must go sir, I got to clean up.’

‘Young fellow, check the carafe in my cabin and keep it filled with the ship’s best wine. Do it and it’ll be worth your while.’

The boy nodded and hurried away and Finnian turned to observe the irate merchant who was fast becoming a blur on the distant wharf. Taking a place tucked against the taffrail, he allowed the voices and the shipboard lingo to drift over him as men worked as a well-ordered team. A crack in the folds of canvas above told him the mainsail had been unfurled and he felt the deck rise like a horse jumping a fence, the wind filling the vast sail, the design of a black fleur-de-lis ballooning.

‘You like my ship?’ A faintly tinged Pymm voice spoke beside him. He turned and found the speaker was a man of stringy appearance, his cheeks a patchwork of red veins.

‘Indeed.’ Intrinsic dislike filled Finnian’s bones. This man had a temper steeped in vitriol, he could sense it as surely as if a faint red mist hung on the horizon. Aine knows he’d had a lifetime of learning what that was like.

‘I run a tight ship. One step out of line and the crew will pay. Laxness and levity have no place on my command.’ The captain’s hands clenched and unclenched on the taffrail and Finnian observed the muscles in the man’s calves bunch beneath his white stockings as he balanced against the burgeoning sea-swell. He turned directly to Finnian and the eyes, close together and small, blinked once above a pinched nose and a mouth flatter than the horizon. ‘I hope you will be comfortable. The cabin boy will run after your needs and I will see you at my table. By the way sir, if you weren’t aware, you only step up to my decks on my explicit invitation. Passengers’ decks are there,’ he pointed to the maindeck awash with men and ropes. ‘I shall let it go this time.’ He dismissed Finnian with a perfunctory nod.

But Finnian mesmered and the captain forgot about invitations. Forgot even that Finnian stood on his precious stern-castle, wandering around, examining and absorbing all that shipboard life offered. To see without being seen, to do without being remembered – an artform peculiar to the Færan, and one he intended to make so much use of now he was away from Isolde’s intimidating presence.

He leaned over the rail and glanced down at the purling wake as the ship made swift progress southerly to the tip of Trevallyn. He knew he carried the weight of a damaged child’s hatred in his soul and there were moments when he wished he could rise above it now that he was free. But his fingers tightened on the polished timber beneath his hands as he reconciled himself to the knowledge that as long as Isolde was alive, he would never be truly safe.

The boat shifted along in the light breeze. He guessed thee speed at four knots. With good winds they could cover about fifty leagues in a day, one hundred and fifty miles, a few less nautical miles. Distance, distance and more. Once in the Narrows the vessel would tack along that cold stretch of depthless water and finally turn to beat northerly up the west coast, heading for the deepwater port of Marino, one of the outer islands of the great canal city of Veniche. His spirit soared with the success of his escape thus far and with the knowledge he had avoided detection. Above him he could see gulls and gannets scooping and swooping in the humid airs and it was only the tiniest movement in the lower corner of his vision that made him look down again at the sea.

A merrow watched him back. Rolling and flipping like some obscene dolphin, he waved his arm at Finnian and then more particularly his finger, which waggled back and forth. The sun glinted on a blade-like fingernail and an unwanted image of stilettos flicked through Finnian’s mind. He turned his back on the malign water-wight, returning to the cloistered space of his cabin to pour a wine.

As they tacked into the Narrows, the journey began to alter. Finnian wondered if he had drunk more than was wise, but who cares? Convinced he was safe from Isolde’s discovery, he became jovial with the crew, pointedly sarcastic and dismissive with the Captain and deferential with the Ambassador, liking the mark he began to make upon the ship. He lurched across the deck as the vessel veered to starboard, the breeze hardening about his ears. She shook herself, listing one way and then the other and he had to grab and hold hard to the rail as a large wave broached the sides and washed across the deck about his feet. He shivered in the dropping temperature, the inkling of ice not far off urging him below to seek wet-weather gear. In truth he craved a storm. Some shipboard wrestling with the elements was surely better than ennui and the doldrums. He rummaged through clothes he had cast around, finding the perfect coat to protect him from the weather but allowing concealment within the shadows of the stern-castle.

The wind strengthened by degrees, the sky darkening and he planted his feet to find the rhythm of the sea, the deck rising and then falling away and a loud laugh bubbled up from deep inside. The Harpies screamed through the shrouds and the sailors made the protective sign of the horns but he urged the Shriekers on as they played with mortal sensibilities, shredding nerves. This was life and even though he was mildly drunk, he knew his mood had more to do with escape than anything.

The wind strengthened by degrees, the sky darkening and he planted his feet to find the rhythm of the sea, the deck rising and then falling away and a loud laugh bubbled up from deep inside. The Harpies screamed through the shrouds and the sailors made the protective sign of the horns but he urged the Shriekers on as they played with mortal sensibilities, shredding nerves. This was life and even though he was mildly drunk, he knew his mood had more to do with escape than anything.

The Captain did indeed keep his crew leashed tight, allowing neither storm nor Others to shatter concentration as excess sail dropped to the deck and dragged at Finnian’s booted feet. The storm-rig was trimmed, the men springing to orders as if a cat o’ nine tails lashed their backs. As the action increased and the deck became slick with wash, Finnian glanced down the stair and caught sight of a white face. The cabinboy’s bleached visage stared back, teeth tearing at his bottom lip. The wind grabbed his blonde curls and lifted them skyward where they stayed, vertical corkscrews, as if he had the fright of his life. A familiar emotion chimed in Finnian’s memory when he saw the pale face and with barely a thought he jumped down the stair, hustling the boy in front of him to his cabin.

‘Here,’ he said. ‘I need some help getting out of my wet coat and boots.’ The silent boy took the weight of the saturated oilskin as Finnian shrugged it back off his shoulders. Sitting himself in the chair he thrust out a booted leg and bade the young chap pull. ‘What’s your name?

‘Gio, sir. Gio Poli.’ He cringed as the boat shook.

‘Do you like being at sea, Gio.’

‘Most times, sir.’ He pulled and the boot came off with a rush, the boy fetching up against the planks.

Finnian shoved up the other leg. ‘When you’ve got this one off you’ll find a dry pair in the chest, you can help me put them on. Tell me, have you family?’

‘Oh yes, sir. My Ma and Pa and me, we all live in Veniche and my Ma is a sought after lace-maker, really good too. The nobles often ask her to do things for them. And my Pa . . .’

The boat pounded off a wave and the boy lurched sideways. Finnian grabbed him and set him to rights. ‘Are your family good to you, Gio? Do they beat you?’ Anything to keep the boy’s mind away from his fear because Finnian knew fear. Does it burn into your gut, Gio, until you feel more scared if your heart stops its frenzy – as if worse things are around the corner?

‘Lor Sir, why would you ask such a thing?’ The boy held tight to Finnian’s leg. ‘I know there’s some who beat their children and it’s a terrible thing and my Pa who is the most gentlest person, he reckons they should be drawn and quartered for such behaviour. But I’ve the best family. I’m the luckiest boy ever. My Ma says she loves me more than life itself even though it’s a bit embarrassing. But anyway when I come home, she cooks my favourite food and tells me all the doings that I’ve missed and even though I give her my earnings, she’ll give me a coin to do what I want. But I’m saving it ‘cos I want to buy her this tiny cameo I saw in a goldworker’s shop and she can hang it from a chain that my Pa gave her when they married.’ Gio propped the wet boots against the walls where they promptly fell again under the weather’s onslaught. The light swung like a dervish and the hammock creaked as it moved in unison. Weaving his way across to the chest, Gio grabbed the other boots and advanced at a run on Finnian who plucked him close as the ship slewed. ‘And my Pa has the best stories to tell because he’s met all kinds. Mortal and Other.’

‘Has he indeed? What Others then?’

‘Oh Færan, hobs, a goblin once, some tiny Siofra who hid in a boat he was working on at the time.’

‘Anyone malicious?’ For the world is full of malicious folk at every turn, young Gio.

‘No . . .’ But then the boy’s face brightened. ‘He saw an urisk once. The fellow just sat on a rock in the middle of one of the marsh rills and played a tune on pipes. Terrible enchanted it was and Pa was going to stuff his ears with some cheese Ma had given him for midday but the urisk saw him and asked what he thought of the music. ‘Plain wonderful,’ says my Pa. ‘As if Aine has kissed the pipes you blow.’ And the urisk bowed and asked if he could share Pa’s meal and Pa knew that to deny such a request was to bring down all manner of ills, so he welcomed the urisk. Do you know what his name was? He told Pa. Can you believe it? Cos name-swapping is bad with Others, so they say. But not this time.’ Gio’s face had brightened, a rosier tint creeping across the wretched shade of earlier. His eyes shone as he told his little story. Finnian nodded his head and the boy continued blithely. ‘It was Nolius although he likes Nolly. He was kind enough to my Pa. Said good things would happen to his son one day.’ He gave a grin of sorts. ‘That’s me. I’m the son.’

Your father met Nolius? Well, well. Finnian remembered the redoubtable urisk who had visited Castello for a short time. A very short time. As he left he said to Finnian, ‘This place is a pustule, a boil on the backside of Eirie. I would get you gone, Finnian. Bigger and better things await outside.’ He had thought then, I would but I can’t get past her.

Gio pushed on the last boot and stood. ‘There, sir, I’d better go to the cook and see if the Captain’s meal’s ready. He eats in any weather.’

The boy’s smile lit the shadows of the storm-tossed cabin as he departed, bravado on the small face. A thick and insidious thread of jealousy floated after him because Finnian envied the child the familial love and care. Something he had craved all his life, something he had never had. It invoked the sour taste of memory and he grabbed a pewter goblet and flung it against the planks. No one would hear; it was just another thump amongst many.

Mesmerising is the only word for it, Mesmered. I loved the contrast between the surface beauty of the seraglio and its underlying ugliness of confinement and cruelty. That came across so powerfully.Lalita is an engaging person, courageous in her fear.

And all this contrasts again with the Finnian chapter, the harsh world outside, of rough men and ships. It was intriguing to witness Finnian’s momentary empathy with the cabin boy’s fear of the storm, though his jealousy of the lad’s happy home-life added a frisson of uncertainty to any assessment of his character.

And fascinating too, the reminders we are on a different world entirely, with the Other creatures that pop up from time to time.

I am impatiently and greedily waiting for more. When you have the time, of course.

Prue…just got to sit down and read this finally! And the first 2 chapters. Yeah, I’m that far behind. Interesting characters these two, Finnian and Lalita. One is escaping a prison to explore freedom and the other is leaving freedom to enter a prison…or that’s how is looks so far. I’m anticipating what happens next! Your vivid descriptions of the sights, feelings, sounds and smells are intoxicating!