Whispering Gallery…

Dorothy Dunnett has been my icon for many years – to any who have followed me on my blog or on my professional Facebook page, they will know that I consider her the doyen of historical fiction, surpassed by no one.

I first discovered her one lazy September about twenty years ago. My children were on school holidays at the time and we were staying at House on the coast and I needed reading matter. Our village has a super little state government-funded library and our family haunted it through the school holidays. It always supplied what we needed, from toddlers right through YA to the adult years…

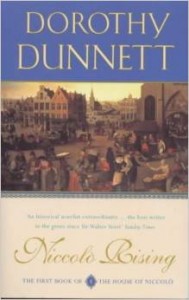

This particularly September, I had a craving for good historical fiction and so I just browsed the shelves from A-Z (it’s a small library…), looking at covers and then flicking over to the back blurb and seeing what set my heart aflutter.I reached the D’s and found a cover that I liked – fifteenth century Flemish and Dutch art has always appealed for its intimate, microscopic view of life at the time.

And a blurb that made the hairs stand on my neck:

The time is the fifteenth century, the Renaissance world of trade, banking and war when intrepid merchants became the new knighthood of Europe. Among them, none is bolder than Nicholas Vander Poele of Bruges, the good natured dyer’s apprentice who schemes and swashbuckles his way to the helm of a mercantile empire.’

The words that so excited me were trade, merchants, Bruges, dyer’s apprentice and schemes and thus I flipped the book back to the front cover to note the author – Dorothy Dunnett – and the title – Niccolo Rising.

I opened the book to the first chapter:

‘From Venice to Cathay, from Seville to the Gold Coast of Africa, men anchored their ships and opened their ledgers and weighed one thing against another as if nothing would ever change. Or as if there existed no sort of fool, of either sex, who might one day treat trade (trade!) as an amusement.

It began mildly enough, the awkward chain of events that was to upset the bankers so much. It began with sea, and September sunlight, and three young men lying stripped to their doublets in the Duke of Burgundy’s bath…’

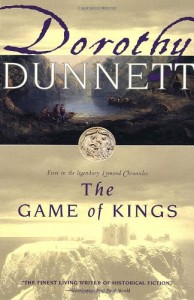

A net had been cast over me and it fell delicately, like silk gauze, perhaps even like filaments of a spider’s web because in truth it never let me go. I took the book to the librarian and she stamped it and I read it in two days. I went back to the city then and hurried to my favourite bookshop – I felt as Lymond must as he craved more opium but of course at that stage, I hadn’t met Lymond. I purchased all six books of The Lymond Chronicles immediately and Books One and Two of The House of Niccolo and I had my name placed on a perpetual order for any new Niccolo’s that the shop received.

Thus I moved from beginning my collection with a small paperback, moving to trade size and ultimately, because publishers were so slow to release trade size … to hardback. Then of course, I had to purchase Elspeth Morrison’s two companion volumes and all books sit on my shelves in the middle row at eye level, hiding my own novels which sit behind them!

Whenever I am looking for a novel to read, when no title catches my eye in the bookshop or on Amazon, I reach for a Dunnett. It’s like a craving, but with each satiation one finds new sensations, minute detail that one may have missed in earlier readings. I subsequently found online that it is a condition suffered (and enjoyed) by many Dunnetts fans.

I decided to join the Dorothy Dunnett Society two years ago, because I wanted access to Whispering Gallery – a journal whose content adds to the historical fact already imparted by Dorothy. And to be frank, who could not be enticed by a journal called Whispering Gallery? It implies secrets (segreta) – something that never fails to interest me in novels.

The day the journal appears in my mailbox is always a thrill. It requires care to open the envelope, and it becomes something of a ‘moment’ – something to be treasured and prolonged. It takes me a few days to read and savour the contents – academic discussion that is presented in such a lively way that fans can read, enjoy and be educated and enthralled.

So perhaps you can imagine my excitement, maybe even my anxiety, when I received an email from the editor of the journal asking if I would like to contribute a 600 word piece on ‘disguise’ in Dorothy’s novels for Talking Point, a section within the magazine. The editor and I had ‘met’ when I had hosted a wonderful guest on this blog, the late M.m Bennetts who described her own private relationship with Dorothy. The Society wished to reprint M.m’s post and contacted her through me.

I wrote the ‘disguise’ piece … a kind of ‘colloquial’ offering because that is the kind of person I am, and in much trepidation I sent it off.

The result was printed in the latest edition.

The following was first published in Whispering Gallery 128, the members’ magazine published by the Dorothy Dunnett Society, and is reproduced (here) with the permission of the Society:

“When Suzanne invited me to write a piece on ‘disguise’ for Talking Point, the characterisation that immediately sprang to mind was Thady Boy Ballagh from The Lymond Chronicles. But the more I thought on both series, the more I realised that disguise is manifest through all fourteen books. It appears to be a frequent and thrilling motif used by Dorothy throughout and I applaud the nature of it. It reminds me of one of my favourite words – ‘segreta’ – secret. For what are Lymond’s and Niccolo’s worlds, but a vast web of intrigues and secrets?

It’s important to remember that ‘disguise’ doesn’t merely mean to conceal by way of dress and/or appearance. The dictionary defines the word any number of ways, but my favorites are ‘to hide the true nature of’ and ‘sham’.

Lymond is the personification of the both – a desperately young man who must come to terms with an awkward and damaging perception of himself. That he is filled with ego is unarguable. That he is articulate is beyond doubt. That he appears unable to process and accept his emotions, all the twisted mass of them, is to me, undeniable. To enable himself in the society in which he moves, disguise is rampant. Sometimes appearance, sometimes behaviour, always ‘dialogue’.

“I wish to God,” said Gideon with mild exasperation, “that you’d talk, just once, in prose like other people.” Gideon to Lymond in Game of Kings.

But everything Lymond does is designed to deceive, to create a veneer, to beguile and dissemble. And all the while, the pace of the narrative is such that we are left in his dusty wake, wondering, so that we must turn the next page.

In addition, Lymond is called by many names – Lymond, Francis Crawford, The Master of Culter, Thady Boy Ballagh, the Vervassal Herald, the Voevoda Bolshoia, and with each manifestation comes a new disguise – a new personality designed to divert interest from the dangerous, and to cultivate support from the unwary.

The same can be said of Nicolas in The House of Niccolo. He creates an alternate persona at the inception of his story by being the fool, under the name of Claes, but it takes very little time for the reader to realise that this man, like Lymond, has an agenda.

‘Underneath all the fright, the bastard enjoys it. Or he’d stop. Wouldn’t he?’ Julius to Tobie in Niccolo Rising.

His disguises may not be as many and varied as Lymond’s, but we are never sure if we are viewing the artist, the musician, the friend of children and the toymaker, the banker, the merchant, or the complete mountebank. Each manifestation enables him to evade trouble, to mask Macchiavellian plans, to enable revenge when he is cloistered on all sides by his well-meaning coterie.

‘Then, when we get to the Palazzo Medici, you imitate his voice and I’ll sit him on my knee and move his arms up and down. Where is the problem?’ Tobie in The Spring of the Ram.

But Dorothy uses the motif of disguise most chillingly and emotively, I believe, with the creation of the two children in The Lymond Chronicles. Is it Kuzum or is it Khaireddin? Even now, we ask that question. In my mind they are disguises, heartbreakingly so, of each other.

In the end, Dorothy employs disguise repeatedly and with consummate freshness throughout these novels and I imagine that when she coined the phrase: ‘Si mundit vult decipi, decipiatur.’ (‘If the world wants to be gulled, let it be gulled.’) in Game of Kings, she did so with a wide smile, knowing that we readers might never view the nature of ‘disguise’ in the same way ever again.

My son introduced me to the Lymond series some years ago. I devoured all the books in such a short time I promised myself I’d re-read them some day. Probably now is a good time.

Madeleine, I think one of the signs of a DD fan is the need to read the books over and over… and over and over again! 😉