Gisborne continues on . . .

I barely slept. I sat up high on the cot despite the good sheets and a finely woven blanket. My head rested against the walls and I curled my arms around my knees and stared into the dark.

The candles had long since melted to stubs and the fire had burned down to embers which cracked and sparked and occasionally flared: testament to the breeze that slid under the door from the hallway outside.

I could barely think of Father. Anger smouldered inside me like the coals in the grate. It would take little to fan it and cause a conflagration.

‘My mother,’ I whispered to the dark, a vision of her clear in my head, her honey gold hair bound in pleats and with a filet of twisted silver and gold around her head. She is . . . was, as beautiful as Eleanor of Aquitaine. My father was lost to her when he met her, just as he was lost now without her. ‘What do you think of this fool man, Mother? Without you he is a rudderless ship, a lost sheep.’ I closed my eyes. ‘A sheep who must follow others in their demeaning games, who must be led along suspicious roads by those who do not have his interest in their hearts. What must I do, Mother mine?’

I prayed and thought how ironic it was that the one time Guy didn’t place me in a religious house for the night was the one night I really needed to pray. ‘Dear Lord. Keep my father from self-harm and keep Moncrieff from the hands of the greedy of this world. Please let me find my home as my own when I return.’ I crossed myself. ‘In nomine Patris et Fillii et Spiritus Sancti.’ My voice crept into the corners of the room and as I followed it with my eyes, I wished that I could see my mother sitting in the chair, that I could ask her advice. But the shadows were dark and I was alone.

I sighed. Khazia.

I blessed her, my dear horse – friend and confidante of eight years. Many a time I had ridden out on my own and told her things I would tell no one else. Why, even on this journey I had chatted to her about Guy of Gisborne. I trusted her far more than I trusted Marais and at least Khazia would not gossip. She knew my soul had begun to stir in response to Guy’s tinkering, that I fancied myself as more than his employer’s daughter. At least a friend, surely. Paramour? The voice that whispered such things lay deep inside my head and I shuddered. But then why should I not allow him into my deepest heart? I had lost almost everything and had nought but a feckless father to whom I must return and maybe a home that was no longer mine. The tears slipped from the corner of my eyes. Guy and I had such a lot in common. He had nothing and no one. Potentially I did as well. We should be kindred spirits, united in our travail through life.

You may have no dowry, Ysabel. That awful voice piped up from the dimmest corner of my brain. For a man who thinks that status is power, what good would you be to him?

‘Be silent!’ I hissed this last. I did not want to know because since my feelings for Gisborne had made themselves felt, I had cherished this obscure idea, one I only shared with Khazia, that I could have given Guy status. As the daughter of the moneyed Baron Moncrieff, I could have given him wealth, a title. My father no doubt thought well of him, he still employed him as his squire and Guy would have attended many of my father’s meetings with other nobles. That he thought Guy was educated and steady was obvious. Why else would he trust him at his shoulder? He would see Guy as the capable son he never had. Marriage was within my grasp.

So I had daydreamed to my horse and her ears had twitched and I remembered now that she had snorted loudly.

Derision. That’s what she had felt. For what man with ambition would want to tie himself to a damsel with nothing? If my father had lost Moncrieff, I would be penniless, landless. I would no longer be Lady Ysabel of Moncrieff but just plain Ysabel, cast out into the bumpy road of life. ‘Oh God help me,’ I whimpered as a likely future stared across the room at me.

I could not bear the thought of Khazia being sold. To me it would be a death. Death of a past life and one for which I would grieve forever. But then my spirits brightened. If it was a religious festival day and business closed, then surely Guy would not be able to sell her. We would have to wait just one more day which meant that she could be shod and we could continue on. The bells of the Benedictine Abbaye Saint Ouen chimed the hour for Vigils and I shivered as I have ever held the belief that the midnight hour is the witching hour. ‘Hail Mary full of grace . . .’ I began and crossed myself again, wondering why this religious fervour had suddenly filled my soul. Briefly I thought that if Father had gamed Moncrieff away, then I had a choice beyond the road . . . I could become a religieuse. Many noblewomen did, for any number of reasons. They might be unmarried, unloved by their family, of ill-health. They may even have a calling. But what they had and I of course may not, was a dowry for the Church. Besides, the thought of being incarcerated in a House of God was not my calling. For some reason, Guy’s face crept into my thoughts and I felt a blush thread itself over my body. Carnal thoughts! I could never become a Bride of Christ. As this idea left the way it had entered, a soft tap could be heard on my door.

I jumped up and ran to it, my heart pounding. Inns were all good and well, but at least one felt safe in the dorter of a House of God.

‘Ysabel,’ Guy’s voice whispered. ‘It is I . . .’

I flung the door open and dragged him in. ‘Are you mad? Everyone shall hear you and I will be seen to be a harlot!’

‘Then it is good that we leave in an hour.’ He bent and stirred the fire and placed a log on it and the room warmed in the firelight.

My eyebrows rose. ‘An hour? But it is dark.’

‘I have found a ducal troupe leaving for the north and we can travel in their wake. It will be safe. They go to meet Richard at Calais.’

‘But what about Khazia?’

‘There is a Comte Andre de Sevignon with whom I have spoken and he was attracted to Khazia for his ladywife. We agreed a price,’ he placed a bag of coin in my hands, ‘and he has also traded me a good campaign horse as part of the bargain.’

‘But the religious law . . .’

‘The bargain was sealed before midnight.’

Khazia?’ I could have wept.

‘Has been taken to the Comte’s estates.’

‘No! I have not said farewell.’ I threw the bag and it hit his chest. ‘How dare you do this without my approval!’

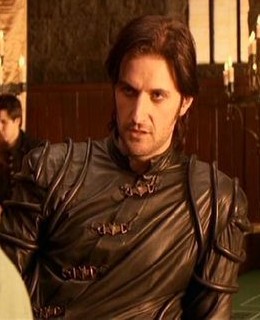

He glared at me, his eyes as cold as steel.

‘As I recall, we decided to leave forthwith for Moncrieff. Khazia, like Marais, was a liability.’

‘Goodness Guy,’ I snarled. ‘Shall I become a liability that you must rid yourself of as well?’

‘You are frequently a liability, Ysabel.’ His voice stroked the hairs on my neck in a frightening manner. ‘Here . . .’ He dropped a bundle at my feet. ‘Whilst I do think you are winsome in your shift with the light behind you as it is . . .’

I jumped and grabbed the blanket of the bed to wrap myself.

He swung his gaze over every inch of my now covered body and there was nothing I liked in that expression, as if he could have had his way with me then and there. ‘Too late, I am afraid. And a pretty view it was too.’ But he sobered as quickly as a wind change. ‘You will be riding a campaign horse and as we are with soldiers, my advice is to dress as a boy. I have leggings and a tunic in that parcel; and some boots and a cap. Your dark cloak is unremarkable and as much a man’s. It will serve. For what it is worth Ysabel, it may pay to be dressed thus until we reach Moncrieff and find out what awaits us.’

I hugged the blanket tight, humiliated, wishing I had never thought I could marry him. ‘Why? What does it matter if a noblewoman rides to the coast along with a ducal troupe?’

‘I don’t know. My gut crawls a little, that is all, and it is better to be safe than sorry. Dress and be downstairs in an hour, Ysabel. I shall have the horses.’

I watched the broad shoulders, straight back and long legs as he turned and then my gaze moved to the back of his head where his hair sat on the collar of his coat. Once again his mood had swung and I would swear he had put me back to where he had me safely positioned before we had sent Marais home. All tenderness gone in a blink of an eye.

I bent to pick up the parcel of clothing. Thoughts of my little mare and of Gisborne’s mood changes must be pushed aside. Guy had heard something to do with Moncrieff, of that I was sure. How, I couldn’t imagine. But whatever it was, I must put myself in his hands and trust him.

I had no option.

*sigh* what a chapter filled with waves of tension. I’m at his mercy too!

I know you are, iz4blue. Dangerously so, just like Ysabel. But the question is, will it be a happy ending for Ysabel? Or for Guy?

Why do I have this horrible feeling that de Courcy sent him?

Oh, my! Anne Marie, that never crossed my mind but it’s way beyond possible. I do not want to think.

And Guy… Well, him being rude and unkind to a lady he has feelings for: Yes, very Gisborne.

So Ysabel is out to play a boy? This gonna be interesting.