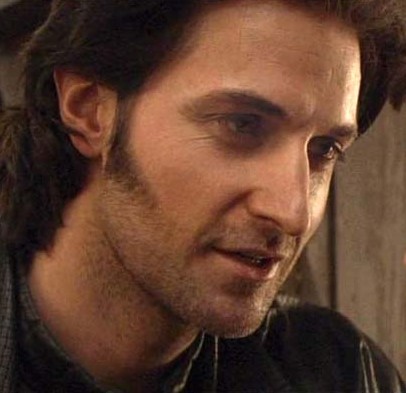

Gisborne . . .

His thumbs stroked over and over across my knuckles.

I woke gently. Sometimes when one wakes, it’s as if ice has been dropped down one’s spine, but I woke as if I were wrapped in silk and wool. Warm, loose, remembering only the stroking of my knuckles. As I arched my body, I knew he had left me, but I felt no fear. Not immediately . . . and then, like the aforesaid ice, cold crept over me and my toes and fingers clenched, my mind recalling death: Wilfred’s, Harold’s, my mother’s. I sat up with a rush.

‘Lady Ysabel, you’re awake.’ Guy strode into the clearing with the horses. ‘I took them to the stream and they drank their fill. There was clover as well.’

My breath gushed out. I hadn’t realised I held it. But his presence eased the distrait of my memories and I clambered up, folding his cloak which he’d laid over me, straightening my kirtle and re-plaiting my hair in a rough braid.

‘Here,’ he said and passed me a handful of blackberries and shelled walnuts. ‘It will have to do. I filled our waterbottles, it’s all we have till Le Mans.’

I rolled one of the blackberries in my mouth, its sharp sweetness filling my mind with berry-coloured memories. ‘We leave immediately?’

‘As soon as we are saddled.’ He shouldered our gear and began tacking the horses.

I swallowed the rest of the berries and nuts. ‘I’ll be back momentarily,’ I muttered, blushing, and dashed to the stream, relieved myself and washed my face and hands. When I returned he was mounted and passed my reins over and I leaped aboard, no leg-up, quite able. But he’d already pushed his own horse on and missed my agility.

***

Alone. Just he and I. Riding abreast. Silent. I could only think he regretted holding me last night and yet I was so grateful.

‘Guy?’

‘Yes?’

‘Thank you for comforting me last night. I was cold and . . .’ I hesitated, ‘so very cold.’

‘It is best bodies lie close when its cold. They warm each other.’

‘Of course.’ Huh, of course, I thought wryly. ‘Where shall we put up in Le Mans?’

‘There is a priory.’

‘For me no doubt,’ I replied with a taste of tart blackberry on my tongue. ‘And you?’

‘An inn close by.’

‘I could stay at the inn as well.’

‘I think not, my Lady.’

My Lady? Lord! After yesterday? I was too tired to argue. All at once I wanted to bathe, buy clean clothes, eat.

‘How long from Le Mans to the coast?’

‘Another few days.’ His mood had become more removed.

Truly a woman would be mad to bother further. I’ve always disliked sulky men. It implied an arrogant individual used to being indulged. And yet this man next to me had not been spoiled.

How did I know when he had told me nothing?

He was my father’s squire.

If he’d led a truly privileged life, he would have never have been a humble squire. And yet I knew he was of noble birth, why then such a humble position by comparison? I knew I could secure answers at Moncrieff, but I have ever been impatient.

I chose my time.

We had been riding by a small rivulet and stopped a few miles from Le Mans. As I dismounted, my foot twisted on a stone I had not seen and I wrenched my ankle so that it swelled dramatically.

‘What have you done?’ He bent to check my foot, my kirtle still hooked up for riding.

Without my leave, he scooped me up to carry me to the water, stripping my hose and boot. ‘Place your foot in the water. The chill will ease the swelling.’

I stood with him holding my elbow. ‘Truly, there is no pain. I am well. May we ride on? I wish to get to Le Mans as soon as we can.’

‘Can you walk?’

I limped slightly. ‘Enough to get me to my mount.’

He sighed as if I were so much trouble, lifted me up and hoisted me back on the horse, slipping my hose up my leg and placing the boot back on with infinite gentleness. I reached to his hand. ‘Guy, I am sorry. This is such a fraught journey. I apologise for being such trouble.’ I meant what I said. I could imagine this squire’s disquiet when my father had given him his orders. Minding me like a nursemaid or chaperone when he could be accompanying my father on hunts and tournaments. Even royal progresses, for my father had a place in the Court whenever Henry chose to visit England. And he could have stood behind my father at the tense baronial confrontations that happened so frequently. Instead he smoothed velvet and minded a precocious woman. ‘Please accept my apologies.’

‘You needn’t apologise. Not when you shoot a bow like a trained archer and when you speak the Saracen tongue.’ His mouth tipped up.

‘You are quite an enigma, Lady Ysabel.’

Me an enigma? I laughed. ‘I shall assume that to be a compliment. Can we go?’

The mood had lightened. In the blink of an eye. And as we rode more peaceably, I took a breath. ‘Guy, why are you my father’s squire?’

Mmmm those blackberries tasted good!

Oh, to be an enigma for that Guy! That means something!

Btw, I’m back! LOL!