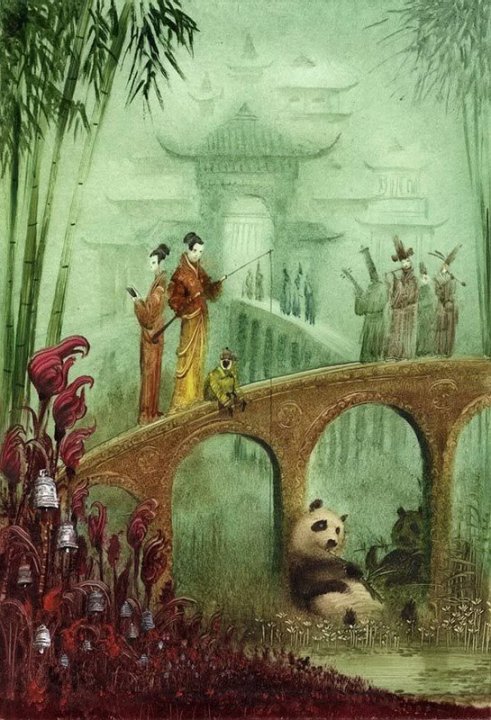

The Shifu Cloth, chapter one.

This is the first chapter of my W.I.P. It is unedited and raw and I offer it up for any comment. It takes place in the secretive Han province in the fantasy world of Eirie. Prue Batten © 2010

Chapter One

Isabella

The ink burned into the paper, the message darkening indelibly as the air settled on the ink-gall. Isabella had slit the bamboo pen into a needle-fine sliver in order to write as secretly as possible. In the silence of deep night the scratching of pen over paper reverberated around the room, so loud she thought the Master or his wife would wake. But the young woman persisted – thin angular letters, short words, with no sign of the begging desperation that drove her to do something that could end in her death if she were discovered. Simple words: Nico, farthest north by northwest.

She lay the pen down on a bamboo tray and removed the tiny saucer of ink, pouring it through the smallest gap in the floorboards in a corner of the room.

Then she began, for the stripping at least must be finished by the time the Master woke. Her work-roughened hands itched and burned as she grasped the bone-handled knife, wincing as blisters split. Bringing pressure to bear, she slit the blade through the paper, slicing friable, infinitely narrow strips. She took a handful of water from the bowl that had been left outside her door during the night, the battered fingers cracking the hoar across the surface as she began to sprinkle scoop after scoop. Each droplet sparkled, flashing as it fell to sink into the paper fibre and she wanted to slow the motion so she could examine the reflection held in the tiny liquid sphere. Her heart wished for some scrying power, as if she would see family, home. But her head knew all that would be reflected would be a bare paper-screened room, mats on the floor, her quilt rolled on top of her sleeping mat and a lantern flickering as the last of the oil burned away.

She took up the strips and rolled and massaged – anyone looking into the room would think they had chanced upon a noodle-maker except that the room lacked the comfort of a kitchen fire or the smell of star-anise, or ginger and garlic. The swollen, reddened fingers lifted the fibrous bundle and she stood shaking and gyrating so the strips separated and fell apart, hanging like an oyster-coloured veil. She could see little of the writing, maybe faintly with the acuity of an informed eye, but she relied on the fact that paper had a memory. She had been told this by her mother when she was young because her Aunt Lalita had been a gifted scribe and knew all there was to know about paper and inks and in her shortened life had passed it to her sister in law who passed it to Belle. Aunt Lalita had said that paper could be cut, even shredded and if the pieces were to ever be re-joined, some sort of bonding occurred. It was possible to see which strip joined where. A harmony, a gathering together of like with like, the need to be side by side with familiars. As well for paper, Isabella thought with an empty heart. But for others like me, no togetherness with familiars at all.

She laid out the strips on the matting and began to draw up one and then another, joining them by pinching the ends and rolling the strips until she had a thin fibre, as thin as thread and as long as forever, dried now in the persistent dawn light but pliant and flexible nevertheless.

On the other side of the winter-cold compound in the family’s sleeping wing, she could hear Madame Koi, the Master’s wife, rattling off complaints in a dialect she could barely understand. Then the slap-slap of the woman’s slippers along the verandah, a door sliding open and then shut and then more rattling as the kitchen staff received the back of her tongue.

The Master’s steps followed, heavier, the paper in the screens vibrating. The door to Isabella’s room slid apart and he filled the space, face in shadow. His quilted black robes smelt of sandalwood, his voice when he spoke, sonorous and not unkind. ‘You have begun. Good. The fabric must be ready in two days, the loom shall be delivered shortly.’ He spoke in the language of Trevallyn and Pymm, each syllable wrenched and masticated and she knew he tried hard so she could understand.

‘Yes Master Koi. It will be ready.’ She bowed her head over hands that she slipped into the wide sleeves of her padded, indigo robe.

‘It is cold. I shall send a brazier,’ and he withdrew, the dark of his robes stirring the embers of memory.

She saw them then, the men and the boats.

They had come at midnight, gliding over the darkly silvered waters like black swans. The moon had hidden behind a curtain of cloud and the boats blended with the shadowy chiaroscuro.

The young woman and her cousin had just pulled in the nets and were bending to fill baskets with wriggling whitebait, the incoming tide brushing over their toes. They chatted to each other, Nicholas deftly flicking crabs and other fish back into the phosphorescent wash. An oil lamp flickered in the breeze, an agitated jump by the small flame that lit their baskets and the piled nets.

She had looked up as a hand slid over Nico’s mouth, an overpowering force encircling his chest. She had no time to scream. A strong force grabbed her – a muffle tied over her mouth, hands pulled back and bound. She struggled, fighting against the arms that lifted her and hefted her over a shoulder. Still she kicked as she was carried through the water. She could hear the dialect, a strange language that chilled her and which accompanied a whack with a closed fist on the back of her thighs. It was only later she felt the ache from the bruise that followed because at that minute she was thrown with no attempt at care into one of the boats. She hit the planks on the floor and screamed and screamed, a muffled sound as weak as a babe’s. They began to pull a bag over her head and she shook her self from side to side until they hit her hard on the temple, a harsh pain following and dizziness as vomit swelled into her mouth. She tried to glimpse Nicholas and saw him kick and punch from the shore. Just before the strange smelling covering slid down over her eyes, she saw Nicholas fold into the unkind shallows of the night.

She lay still in the moving boat, her heart pounding, knowing each beat took her further and further from all she held dear and for the first time in her life she knew fear like she had never felt before. Her life had been built on a simple foundation stone – she knew who she was, everyone else knew who she was and there had never been any need for confusion or effort. Nico had told her again and again that such thinking led to arrogance. Even then, as the boat moved away, her heart beat in time to his words: ‘Pride goes before a fall.’

The seasons had passed and with them her pride had fallen like leaves from the trees in autumn. She had entered the compound when the elm was a spider-web of barren twigs, snow settling like a white shroud. Spring brought forth acid green bud and unfurling leaf. Summer elicited shifting shade and then autumn arrived dipped in topaz and toffee. And now winter again and she had cried so much, she thought she would wither from the dryness that crackled inside her.

Isabella, whom they called Ibo, was their slave. She had skills.

In Trevallyn and Pymm she had been fêted not just for her ability to work in the field, but for her embroidery, her sewing, her delicate writing, her skill on the lute and for her lovely face. Here, wherever here was, farthest north by northwest, she was valued in a different way for those same things. The House of Koi paid the slave-master handsomely for her hands, even though the Master’s wife punished her for her face.

Isabella moved to a bamboo basket filled with copper hanks of silk. It was she who had suggested stripping some of the bark from the elm in the gardens and boiling it to see what colour emerged. The shade had been a little of sunset and sunrise but needed more depth, so she split apart an old wasp’s nest from the garden. Inside some little creature the Han called vermilac had spread, bred and died by the hundreds and their dried husks were boiled to release a colour as richly red as the lacquer of Master Koi’s trays. She added it, drop by drop, as if she were some scheming alchemist of old. Then one drop only of oak gall and there it had been – her mother’s hair colour glinting like new-minted gelt. She had prepared a simple woven square and hadn’t shown the Master until she had observed it in all the lights of day and night and was content that it glistened and glowed as if it had been sliced from a beam from the heavens. He immediately desired a bolt, for he saw his family’s fortunes rising like the sunlight of Isabella’s dye, the fabric to be sold at the prestigious Stitching Fair in Trevallyn. Now here she was, grasping the fibre of the paper and threading it through the loom on the weft, with the copper silk on the warp and without stopping for breakfast or a midday meal and then only briefly for a bowl of savoury dumplings in the night, she continued on.

The tsk-tsk-swoosh, tsk-tsk-swoosh of the loom counted off the minutes of her life and she felt the shifu cloth falling onto her feet. At one point she pulled up the yardage she had woven and examined it for signs of her words. Her finger slipped over the faintest slub and she knew it was a letter and her heart sang and she spoke to the fabric as she replaced it carefully at her feet. ‘You have a memory, let Fate put you in the right hands and you will spill your memory forth, so help me!’

Ah, Prue, that’s lovely. It fills me with happiness and excitement, and you get better all the time.

Write faster!

Pat, there are such things as coaches and you are one of the best I know to keep me on the straight and narrow!

whoa, sounding good. i love this –> paper had a memory.

When I was doing a post-graduate course in the paper-mill (since closed through lack of foresight) here at the University of Tasmania, our lecturer, Penny Carey-Wells (internationally acclaimed book and paper artist) told us that paper did indeed have a memory (ie grain etc) and the words stuck in my brain and I manipulated them, as one does in book and paper art, to suit my purpose in this book of fantasy.

But shifu-cloth is actually historically real. Used in Japan at the time of the samurai to transmit secret messages across the provinces safely.

Shall put up the next chapter soon, which begins Nicholas’s story. The two stories run parallel and then converge.

Prue,

I don’t usually read fantasy so I don’t know how valuable my opinion would be but I truly loved it!

I can’t wait to read more of Isabella’s story…

Thank you Lua. It’s been a hard story to write because of the lack of continuity. So many breaks . . . with demands from the previous story as it moves forward in its life to submission. One tends to get so lost in technical detail, that one forgets the real thing is actually a ‘story’. So your thoughts are so appreciated . . . particularly when you don’t read the genre. If you liked it, presumably you liked it as a piece of writing and for that I am grateful.